Part I:Science

Before digital cameras made it easy to capture a rare bird, the tools of observation were pencils and brushes; before Google Images, scientists and students turned first to the great works of scientific illustrations. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art and science are so closely related in the zoological fields that it becomes difficult to separate the two; one could no more imagine the great zoological journals without their plates than a zoo without the animals. The period of time between 1700-1900 can be called the Golden Age of the natural history book.

The single greatest influence on all subsequent bird and animal books was the French polymath

Buffon. He was born in Burgundy in 1707 and was incredibly talented as a naturalist, mathematician, and cosmologist. His greatest work was

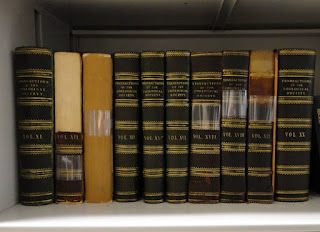

Histoire Naturelle, a 44 volume encyclopedia describing everything known about the natural world. He proposed 50 volumes, but only 36 were published before he died in 1788. Ultimately 44 volumes were published. Here is a picture of the Museum’s set of Buffon.

This massive undertaking described everything known about the natural world. 100 years before Darwin, Buffon pointed out the similarities between humans and apes.

Another early naturalist that influenced the masters of illustration was

Mark Catesby. Catesby was born in 1679 in England. He traveled to America in 1712 to study the flora of the New World. After a second trip to America, he returned to England for good in 1726 and taught himself etching. His work,

The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, was published as a large folio between 1731-43. It includes 220 hand-colored engravings, 109 of which are of birds. This was the earliest book with colored plates to include American birds, though printed and published in London.

Catesby was not a particularly talented artist, but his naive pictures are charming and colorful. Catesby liked to display his animals and birds in their natural habitat and to include the plants that were the source of food; for each plate, he described in great detail not only the bird depicted, but also the plants and other animals.

Many of the most-admired artists and illustrators got their start by illustrating the publications of the

Zoological Society of London. The Society was formed to create a collection of animals for study at leisure, in other words a zoo, as well as an associated museum, and a library. The Society produced both

Proceedings and

Transactions, and they were heavily illustrated by some of the most famous natural history artists. As you can see here, the Museum’s set of Transactions has seen better

days; their wear and tear clearly shows how heavily they have been used

as a major scientific resource.

One of the most prolific artists to work for the Zoological Society was

Joseph Wolf. Almost as soon as the Society decided to illustrate its

Proceedings and

Transactions, it hired Wolf to do the job. He produced around 340 illustrations for the Proceedings, most between 1850-1865, and he did around 30 drawings for the Transactions, which were published irregularly. These are lithographs and then hand-colored, created from water-color sketches. In some cases Wolf had live animals to work from, but in others he had only skins or specimens preserved in bottles of alcohol.

Here are two illustrations Wolf did for an article on falcons:

The last of Wolf’s drawings in the Transactions were from life, and they accompanied the paper “On the Rhinoceroses now or lately living in the Society’s Menagerie” by Philip Sclater, published in 1877. Sclater presented the paper to the Society, saying: “The main object of my remarks on the present occasion is to illustrate the very beautiful drawings by Mr. Wolf now before us.” You can certainly see why Sclater was so impressed by Wolf's talent when you take a look at these two illustrations:

Wolf's detailed observation of animal behavior led to his collaboration with Charles Darwin on the book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Here is an example of his work showing facial expressions of monkeys.

In the 1830’s,

Edward Lear was the unofficial artist in residence at the London Zoo. He illustrated scientific articles that were published in both the

Proceedings and

Transactions of the Zoological Society of London. Here are some examples of his work illustrating mammals for various articles in the Transactions. The first image shows an illustration Lear did for an article presented at the Zoological Society by Mr. Ogilby on a new genus of carnivores, closely related to the mongoose. Note the diagrams of the animal’s skull in the upper right.

Here is Lear’s illustration for Bennett’s article on a new species of kangaroo from New South Wales. Note the side view of the skull showing the teeth.

When he was just 18 years old, Lear began a project that established his reputation as one of the foremost natural history painters. It was his idea to illustrate and publish a book on the parrots of the world. Working from live specimens at the London Zoo and in private collections throughout England, he spent the next two years making hundreds of spectacularly beautiful-and scrupulously accurate-watercolor studies, eventually publishing 42 of them as lithographic prints to be bound together in book form in 1832 (when he was just 20 years old!).

This ground-breaking work was the first bird book to be published in folio size and the first to focus on a single family of birds; it was the first in which all of the specimens were drawn from life, and one of the first to use the relatively new process of lithography, rather than engraving, for illustrations.

Only 175 of these books were ever published. Fewer than 100 copies survive today. Unfortunately, CMNH is not one of those lucky owners, but this work is so important and so beautiful that I had to show you some examples.

Lear’s career as a bird illustrator was cut short by failing eyesight, so he turned his talents to writing nonsense. Aha - so that’s why his name sounds familiar! He was the author of The Owl and the Pussycat, from A Book of Nonsense, which was published in 1846 when he was 34. He lived to see 30 more editions published before he died.

John Gould was another author/illustrator who got his start at the Zoological Society of London. Before his days as an author and illustrator, Gould was a taxidermist. He set up his first business in Windsor, and quickly won recognition for his ability to make his subjects look "natural." He became so adept at the trade that he was commissioned to stuff King George IV’s pet giraffe.

In 1827 he was hired by the Zoological Society to take care of their birds. In 1829 he published the first of his nearly 300 scientific articles; he not only illustrated articles written by others, he also wrote a fair number of scientific articles himself on research he conducted at the Zoological Society.

While at the Zoological Society Gould received a collection of Himalayan bird skins and decided to write and publish a book on Himalayan birds. Gould couldn’t find a publisher, so he published his first book, A Century of Birds from the Himalaya Mountains at his own expense. His wife, Elizabeth, lithographed Gould’s own drawings, a process she learned from Edward Lear, who would later assist the Goulds in many of their subsequent books.

Gould and Elizabeth visited Australia to gather specimens for a new undertaking. He wrote the Birds of Australia using specimens he collected during this trip. Here is an emu from Birds of Australia.

He also wrote the

Mammals of Australia, based on his findings while in Australia. Two examples show a koala and a platypus.

In his lifetime, Gould went on to produce 15 major works on birds, containing over 3,300 color plates. In addition to the works on Australia, these include the birds of Asia, Europe, and Great Britain. Gould’s volumes on the Birds of New Guinea include the magnificent birds of paradise. Except for his collecting experiences in Australia, Gould relied on others to send him specimens for his books.

Perhaps most famous are Gould's beloved hummingbirds, which became his lifelong obsession. By the time of his death, he had amassed a collection of 1,500 mounted and 3,800 unmounted specimens – all having been sent to him by various collectors from around the world. He began his magnificent five-volume

Monograph of the Trochilidae, or Family of Humming-birds in 1849 and finished it in 1861. It is considered by many to be the culmination of his genius as an ornithologist and publisher. At the time, Gould’s monograph provided the definitive reference work on the hummingbird family; it was the most reliable attempt so far to arrange the species systematically. Even Darwin found Gould’s comprehensive work on the hummingbird particularly useful, since it showed the geographical distribution of various species.

In addition to being a useful scientific monograph, the artistry involved in depicting the hummingbirds was stunning and lavish: on every page the birds’ tiny bodies are shown in brilliant colors of electric blue, emerald green, bright scarlet; their breasts and heads were glazed with varnish or gilded with gold leaf so that they shimmered in the light.

Gould was sometimes called the English Audubon. However, he was a better businessman than artist. He achieved his great fame and fortune by publishing his own works and selling them to subscribers. He used talented artists as illustrators, such as his wife and Edward Lear. He died in 1881, leaving a priceless legacy of beauty and scientific knowledge. His epitaph, which he chose, reads “John Gould the Bird Man.”

The Museum is fortunate to own 42 volumes of Gould’s works, all of them donated by Mrs. Dudley Blossom.

The works of

Daniel Giraud Elliot, an American zoologist and a founder of the American Museum of Natural History, mark the end of the period of great bird books. His

Monograph of the Phasianidae (Pheasants) was published in New York in 1870-1872.

It is widely

considered to be one of the greatest illustrated bird monographs, and features hand-colored lithographs by Joseph Wolf; it is folio sized, and Elliot wrote the text. The illustrations capture the splendor and richness of the Pheasant, a most exotic bird that found its way to America from Asia. Elliot was so impressed with Wolf's incredible work that he dedicated the entire book to him. The Museum owns a copy of this impressive two-volume work.

In 1883, Elliot published

A Monograph of the Felidae, or Family of Cats.

This treasure is one of the most important works on the subject ever

published. It contains 43 hand-colored lithographs by Joseph Smit, from

drawings by Joseph Wolf. The Museum also owns this valuable work.

And now for something a little different: this artist started a long career at age 8, studying and recording the characteristics of a wide variety of animals, birds, and insects in a home-made sketchbook. Drawn to the delicate and complex forms of insects, this artist became an amateur entomologist, making frequent visits to the Natural History Museum in London to study and sketch the insect collection.

This artist often used a microscope to do close-up studies of specimens.

During the 1890’s, this artist concentrated on fungi, and became a self-taught expert. Many hours were spent learning everything about mushrooms. In fact, this artist even prepared a scientific paper on the germination of spores, which was presented at the

Linnean Society in April 1897. Only, this artist was not allowed to present the paper, so it was presented by someone else. Why?

Because she was a woman. Has any guessed the identity of this secret artist? Does this illustration help?

Beatrix Potter’s keen observations of the natural world show up in her animal stories. Throughout her life she was guided by the principle of portraying nature as accurately as possible. Her early passion for science was integral to her method as an illustrator.

Beatrix Potter’s theory on the germination of mushroom spores was initially rejected by the Linnean Society, but experts now consider that her thesis was correct. 60 of her paintings were used in 1967 to illustrate Dr. Findlay’s

Wayside and Woodland Fungi.

Part II: Exploration

Most of the artists we’ve seen got their start illustrating scientific publications, such as the

Transactions of the Zoological Society of London. These scientific illustrations were vital to studying and understanding the natural world. When explorers set out to map the world, scientists and artists were on hand to translate their findings into visual descriptions. The Museum has a number of finely-illustrated books of exploration in the Rare Book Collection that make for thrilling reading.

We're going to focus on the illustrations from one adventure here - those of the Challenger Expedition. Modern oceanography began with the Challenger Expedition of 1872-1876. The Challenger was the first expedition organized specifically to gather data on a wide range of ocean features, including the marine life and geology of the seafloor. At the time of the Challenger, all of the Earth’s major landmasses and most of the minor ones had been “discovered,” but almost nothing was known about the nature of the deep seas.

The voyage was the brainchild of two biologists: Professor William Benjamin Carpenter from the University of London and Charles Wyville Thomson, professor of natural history at the University of Edinburgh.They convinced the Admiralty that what was needed was a properly equipped global expedition to investigate the last great geographical unknown on Earth.

A ship was selected and extensively refitted with purpose-built laboratories, accommodations, winches, and the latest equipment, including more than 249 MILES of rope!

The ship’s captain was an experienced surveying officer, George Strong Nares, supported by a naval crew of about 225. The civilian scientific staff of six was headed by Thomson as chief scientist, and included a chemist, three zoologists, and an artist.

The ship traveled south from England to the South Atlantic, and then around the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa. It headed across the southern Indian Ocean, crossed the Antarctic Circle, and then to Australia and New Zealand. From there, the Challenger headed north to the Hawaiian Islands and then south again to the southern tip of South America. The ship spent 713 days at sea and visited 362 official sampling stations. At each station along the way, the crew lowered trawls, nets, and other samplers to different depths, from the surface to the seafloor, and then pulled them back onto the boat loaded with animals or rocks.

Once the specimens were on board, the ship’s scientists went to work documenting their discoveries.

Here are some of the artistic illustrations of just a small sample of their finds.

The Cleveland Museum of Natural History had its own major scientific expedition. In 1923, the Museum launched the Blossom Expedition, a 20,000-mile nautical journey through the South Atlantic Ocean. The journey was financed by Mrs. Dudley Blossom, and after nearly 3 years, the crew returned with 12,000 specimens, 3,000 of which were birds. The expedition visited several isolated locations throughout the South Atlantic including the Cape Verde Islands, the coast of Africa, Saint Helena, Ascension Island, Trinidad and sites in Brazil. Over the years, many of the original specimens from the expedition have been provided or traded to other scientific institutions for further study; many remain within the Museum’s vast collections. By the time of the Blossom Expedition, lithographed illustrations had been replaced by photographs, and the Museum has hundred of photos that were taken on the Expedition. But that’s a topic for another talk/blog post!